The roaring sound outside woke me up. Our house exterior is buttoned up, but the buffeting wind still roars. Another windy day in the Foothills. Our small weather station was showing gusts of 20+mph and one topped out at 41mph. Had we set the anemometer out in the meadow, I’m sure the readings would have been much higher, but it’s attached to the porch roof and represents the gusts we get right here. The National Weather Service will register high winds near 100mph for various areas around the state with this wind event and the news will note damage to trees, houses, and semis tipped over on the highways. It’s the kind of day to keep a good grip on door handles and bring in things outdoors that might blow away. Sometimes, meteorologists jokingly call these ‘small dog warning’ days. Hang on tight. I tried to walk our not-small dog, but once out on the road, we faced a wind tunnel of dust and snow hitting our faces. The dog hates the feel of wind lifting her thick fur and we soon turned around, back to the shelter of the house.

Protected from those elements, we watched our large trees swaying, but not yet breaking. We scanned the forest for limbs down. They are strong though, and have evolved and adapted to the wind that shapes and strengthens them.

Wind itself is neither bad nor good. It is a reality of life on planet Earth. The push and pull of heated and cooled air rolling as the planet turns on its tilted axis.1 (For a more detailed explanation of wind, see the footnote.) It has no malicious intent and it serves life, but it can take life as well. It can blow wildfire smoke in from two states away, and it will blow that smoke out. For our part, we strive to understand it, measure it, enter it into our culture, and manage our lives with it as all life on earth has done.

So, let’s break down some understanding of the wind as it pertains to the Colorado Foothills and other land-based areas.

HUMAN: Since we are all born into a windy world, and presumably, no one, is untouched by wind, we have sought ways to define it, measure it, and harness it. Ancient and modern mariners, pilots, surfers, and insurance adjusters, have relied on wind scales to make decisions.

• There’s the Beaufort scale, from 0 to 12, no wind up to hurricanes

• We can use miles per hour as I stated above.

• Windsocks are a visual, very simple, but effective, scale of strength and direction.

• From sailboats to wind turbines, wind affects and powers many things that make human life easier, and harder.

But, I’m here to look at the wind’s effect on the natural world.

ECOLOGY: Here is where brilliant natural adaptations and innovations are shown.

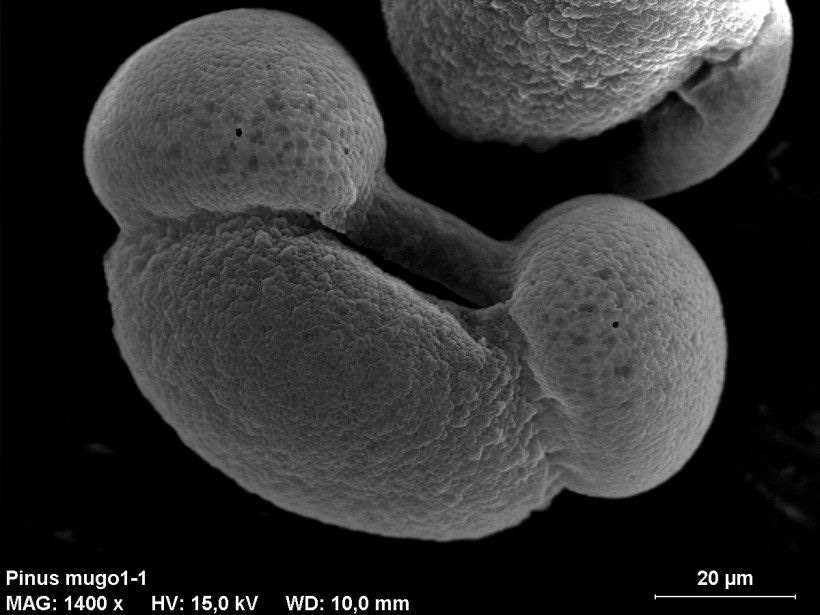

• Pollination - Here in the Foothills each June, our lives are covered in shades of yellow as the Ponderosa Pines send up massive clouds of pollen. You can watch yellow clouds descending on your house. Trillions of little sperm cells called gametes are sent off to land on other Ponderosa Pine tree seeds (and everything else). Pollen, magnified, show sacci, porous and cupped areas that catch the wind and stay aloft, adapting to use the wind to travel. Conversely, many conifers have pinecones that are shaped so that the breeze will blow the pollen around in a swirl to catch as much as possible, these designs are linked specifically by species, like puzzle pieces. Many plants, up to 20%, use wind pollination, they are those plants that don’t produce a bright flower to attract pollinating insects, many trees and grasses are among these.

• Seed transport - From Dandelion puffs to whirligigs, we are all familiar with a plant’s brilliant seed adaptions to ride the wind. Anemochory is the term for these travels and pappus are the tufts of hairs on a seed that grab a ride on the wind to a new destination.

• Plant and tree strength - Watching our big trees sway in high wind gusts, it is also strengthening them, as long as the wind is not too strong. Much like the effects of exercise strengthen our muscles, the wind pushing on trees and plants releases a hormone, auxin, that causes the elongation of cells and stimulates growth from the trunk and limbs, down to the root systems. Even seedlings, just inches high, need to ‘harden off’ by being exposed to outdoor winds. They become stronger in both resisting the forces of the wind, but also in using air currents and nutrients that blow their way. Plants and trees that have grown in windless indoor environments have been noted as weakened and are easily broken or tipped over. So, here’s a word for you: Thigmomorphogenesis. This is the phenomenon of plants and trees responding to physical, mechanical elements in their environment causing adaptations, triggering cellular mechanosensors, biochemical signals that they respond to in how they grow. The twists in the tree trunk are one of the most visual effects of this. Like much of life, what doesn’t kill you, makes you stronger.

• Air Circulation - air moving around the plants can help to dry moisture, reducing the possibility of fungal diseases. As air moves, it can cool a plant, and move nutrients in the soil to them.

• Insect/spider travel - Fans of E.B. White’s Charlotte’s Web know the ending where nearly all Charlotte’s children send up strands of gossamer silk threads that are caught in just the right breeze conditions and float them off to new homes. This adaptation is called ‘ballooning’ and the spider will form a triangle of silk with their hind legs while in a handstand, then release it and let the breeze, along with rising thermals and electrical fields, take them up and away, carrying them anywhere from a few meters to possibly a thousand miles if they get caught up in the jet stream.

• Predation - Bunnies, squirrels, and most of the common rodent family, know well that the breeze will carry their scent and be detected by predators. So they will limit their activity on windier days knowing that their likelihood of being caught goes up significantly. Scientists have noted that a typical predator’s rate of successful catches (feeding events) goes up by 40% on those days when they can catch the scent on the breeze. Calm days to windy will affect wildlife activity.

Too much wind - Hurricane winds damage coastal areas. The Santa Ana Winds caused the recent LA fires to move and explode at alarming rates. Tornados tear up midwest towns. Storms at sea capsize ships. A phenomenon we get here in the mountains is the Blowdown, consisting of straight-line winds (not rotating like a tornado) topping 75 to 100mph and higher that result from strong cold fronts in layers of air masses colliding. (Yes, that is ridiculously simplified.) The brunt of this hits an area of trees taking down nearly all in the path. Yet, now, this area creates a patch in the forest that will be in active wood decay and the breaking down of nutrients, getting additional sunlight, and giving way for new growth. What is destruction at first, can be an avenue for new life.

I made a purposeful twist by referring to Bob Dylan’s Blowin’ in the Wind song. A 60-plus-year-old anthem on civil rights and the futility of war, not only points to the relentless concepts that have not blown away in 60 years but also to point to the concept that the wind is something that requires adaptation and use. Our understanding of the natural world’s adapting to relentless forces can cause us to learn to adapt and use as well. While injustice and war have not blown away, progress has, and will, blow in as well. It shows the necessity of constant change for constant growth. All things are more complex than can be summed up in soundbites and memes. Aiding life and destroying are always moving, always blowin’ in the wind.

📷 All photos are credited: The Abert Essays unless otherwise noted.

📱 Join me on my Facebook page, Substack Notes, and my new BlueSky page. I post smaller ‘Encounters’ posts there as I see flowers, animals, weather patterns, and anything else that catches my eye.

Sources:

- https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/wind_is_essential_to_natural_processes

- https://www.brandywine.org/conservancy/blog/wind-pollination-social-distancing-plant-world

- https://yakari.polytechnique.fr/Django-pub/documents/delangre2008rp-1pp.pdf

- https://libanswers.nybg.org/faq/223076

- https://woodlandinfo.org/wind-damage-to-trees/

- https://stormwise.uconn.edu/2017/05/08/wind-and-trees-101-to-touch-a-tree/

- https://www.lamtree.com/wind-and-trees/

- http://woodlandsteward.squarespace.com/storage/past-issues/windaffe.htm

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beaufort_scale

- https://www.cbs42.com/news/15000-trees-toppled-in-colorado-blowdown-during-190-mph-jet-stream/

- Botany in a Day: The Patterns Method of Plant Identification, 6th edition, Thomas Elpel, HOPS Press, 2021

A better explanation of wind from my Planetary Sciences son: "Wind occurs because pressure is proportional to heat; more heat means more pressure, and, you've probably noticed, not every part of Earth gets the same amount of heat from the Sun. Near the equator, where the sun's heat is most intense, warm air expands and rises. As it does, though, it leaves a gap, and, like the crowd in a packed mosh pit, more air immediately squeezes in to fill this gap. That leads to low-level winds converging on the equator while, at higher altitudes, this air travels about 30 degrees north or south before it cools down and sinks, eventually smashing against the surface, causing high-pressure, diverging low-level winds (as well as drier conditions) around these latitudes. That's only part of the story, though, because the Earth's rotation also plays a part. Picture throwing a tennis ball off the side of a moving train; the ball won't just fly straight out and away, instead, it will, in large part, continue the way the train was moving. It's the same for air moving from the equator, where the Earth rotates faster (see Bill Watterson's Calvin and Hobbes comic where Calvin's dad explains this on a record player https://www.gocomics.com/calvinandhobbes/2020/06/02?comments=visible#comments ) to the slower-rotating poles; it's going to retain that same rotating velocity, but now everything around it is moving slower; because the Earth spins counterclockwise when viewed from the north this means, at least in the northern hemisphere, that the air appears to curve to the right. Now, if we imagine that someone on the ground next to our train throws the ball back to it, the train will speed ahead of where the ball is, and the ball's path will appear to curve to its right relative to the train. This means that, regardless of whether the "pressure gradient force" as it's called is pushing the wind south-to-north or north-to-south, this Coriolis effect, in the northern hemisphere, will always cause it to curve right. This has a counterintuitive result: rather than moving from high to low pressure, the wind, particularly at middle latitudes is geostrophic, meaning that the balance of pressure and Coriolis forces causes it to blow along the equal-pressure contour lines often drawn on weather maps."