My apologies to the Mountain Area Land Trust for the delay in getting this post out. Spring, well, has sprung, taking my time with it. For everyone - joining an event with Mountain Area Land Trust (MALT) is a great day.

A gaggle of us nature nerds gathered at the Patrick House Trailhead in Genesee on May 15th. We arrived for a hike and talk from Denver Mountain Parks rangers, in partnership with the Mountain Area Land Trust, to learn more about Denver’s unique bison herd.

If you live on Colorado’s Front Range, Foothills, or mountains, you’ve likely driven by the herd countless times traveling on Interstate 70 by the Chief Hosa exit 254. But have you stopped and enjoyed the easy hike and fascinating view of the herd?

It was calving season, with at least 11 born so far this spring (and likely a few more by now). This gave us a unique opportunity to see the bison calves, often called ‘red dogs’, based on their size, color, and behavior. Like most young, they follow their mamas and feed often, band together, and push each other around. They nap a lot and get the ‘zoomies’ just like puppies.

These dog-sized, reddish bison will grow up to be the largest land animal in North America. Up to 2000 lbs for the males, with those sharp horns. An adult bison can run up to 35 miles an hour. So they mean it when the fence says, ‘stay back at least 3 feet’. The ‘fluffy cows’, as the National Park Service likes to call them in their safety messages, will be quick to defend their young and remove irresponsible tourists who are bothering them. Respect the horns, the speed, the size. Don’t become a headline about stupid tourists. So, yes, don’t pet the fluffy cows!

Bison safety PSA aside now, there is much to learn about why Denver has bison at Genesee Park. In case you’re wondering, nobody, except perhaps the most pedantic, cares if you call them bison or buffalo. When French fur trappers first encountered these huge creatures as they moved west, they likened them to Water Buffalo, hence ‘Le Bœuf’. Buffalo is considered the more common name, while bison, the scientific name.

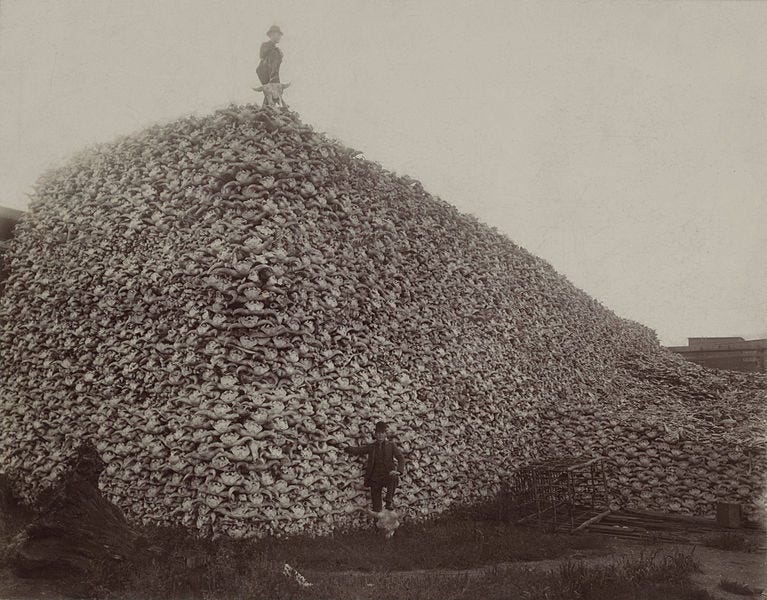

A little time-travel back to the late 1800s in the American West now. The resources available in this wide-open place gobsmacked those who traveled west to see it. All things were seemingly endless; the bison roamed the plains by the tens of millions, the huge trees, the beaver, turkeys, geese, ducks, and birds darkened the sky, migrating in flocks so great that they would break tree branches when they all decided to roost at once. The open space, the open sky, it was almost too much to take in, and the railroads brought the people further into the land and all that it harbored. This was a time of gross indulgence, beyond kids in a candy store. Greed and the assumption that the resources would never end took hold amidst what many referred to as ‘manifest destiny’. Who would care or know if we shot a few birds out of the millions? Who would care or know if we shot bison from the train just for sport? There are millions more. Until there wasn’t.

Market hunting, industrializing the taking of meat, hides, and other resources, sped up the declines in the final 20 years of the 19th century. In just 50 or so years, the Passenger Pigeon, once numbering about 3-5 billion, had its last wild bird shot in 1900. By 1908, there were only 18 bison left in all of Colorado, and they were at the Denver Zoo. There were fewer than 1000 bison left in all the plains states. The giddy greed of the 19th century turned to the sober reckoning in the 20th. Preservation was needed before extinction, not to go the way of the Passenger Pigeon. Mankind’s relationship with the natural world began a seismic shift. (I have mentioned this in several other blog posts.)

What was lost when the bison numbers dwindled was an effect on the entire ecosystem of the plains, since the bison is a ‘keystone’ species.

• Native grasses grow deeper and can handle the grazing of the bison, and even thrive on the saliva left behind.

• Grazing leaves clumps of grasses at differing heights provides nesting and living areas to hosts of animals, insects, birds, and reptiles.

• An area where a bison has rolled in the dirt - a wallow - can create sizable divots that will pool rainwater, which is helpful to all the creatures and plants.

• Many birds used bison fur for their nests and even created protected nesting areas near ‘buffalo pies’.

• Prairie dogs have had a long history partnering with bison, from short grasses to see predators to water availability.

• Bison fur picks up a wide variety of seeds, redistributing them.

• They plow through snow drifts and create highways for other animals to pass through in the depths of winter.

• For large and cooperative predators that can take down a bison, this is a boon of nutrition and provision. A bison’s body can feed many animals, insects, vultures, and other carrion.

• The relationship between indigenous people and bison is deeply integrated in nutritional and cultural health. Heartbreakingly, the purposeful killing of bison was a calculated way to drive tribes away from their homes.

As ecologists readily point out, if you pull one piece, one thread, of the larger picture away, it affects everything down to a microbial level.

In 1914, the Denver Zoo herd was moved to Genesee Park, land that had only been purchased by the city two years earlier. As the herd grew, by 1938, Daniels Park, south of Denver near Sedalia, became home to a portion of the growing herd. The Rocky Mountain Arsenal and many private ranches now keep the bison numbers growing. Current estimates are around 500,000 bison in the nation, a good number, but less than 2% of what once roamed the heartland of the United States. Now, officially noted as America’s National Mammal since 2016, conservation will continue to help the bison thrive.

And what to do when the herds grow to more than the park can handle? Until 2021, bison were auctioned off to private ranchers routinely. In 2021, an agreement was established to donate the surplus bison to the Cheyenne and Arapaho peoples, to help in the reintroduction of bison to indigenous lands in Oklahoma. A step to restoring a bit of what was lost and an avenue for provision and research.

So, make a little stop at the Chief Hosa exit on Interstate 70, and take a little walk. Bring your binoculars and a good camera. Perhaps you’ll get to see some ‘red-dog zoomies’ and learn of the spooky legend of the Patrick House.

Sources:

Our Kindred Creatures: How Americans Came to Feel the Way they do About Animals Bill Wasik and Monica Murphy, Alfred A. Knoff, New York 2024

Mountain Area Land Trust. https://savetheland.org/

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/where-the-buffalo-no-longer-roamed-3067904/

https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/bison-reintroduction

https://www.doi.gov/blog/15-facts-about-our-national-mammal-american-bison

📷 All photos are credited: The Abert Essays unless otherwise noted.

📱 Join me on my Facebook page, Substack Notes, and my new BlueSky page. I post smaller ‘Encounters’ posts there as I see flowers, animals, weather patterns, and anything else that catches my eye.

One of my paid subscribers, George, sent me a link to a blog post he wrote almost 20 years ago. It discusses the hard truths about our western ideas with wildlife, and 'wild people', and also tells the story of Nickel the Bison. Worth the read! https://georgeindenver.wordpress.com/2009/03/02/killing-coyotes-a-gruesome-perk-of-the-privileged/