Note: The following is the research for my final project with Denver Audubon’s Community Natualist course which completed, today, Oct 20, 2023. I highly recommend this type of course if it is available near you.

What is Mistletoe?

Mistletoe is a plant that grows exclusively on host trees. It is a hemiparasite, living off the host tree’s water, glucose, minerals, and other nutrients. ‘Hemi’ meaning that it can photosynthesize somewhat on its own, but not enough for the food it requires.

There seems to be much debate about the number of species of mistletoe worldwide and in the US. As many as 1300, or consolidated down to 26. 5 species are found in Colorado. Many varied tree species are affected by mistletoe infections.

In Europe, a species of mistletoe grows green and large. It is harvested, wrapped with a bow, and celebrated with Christmas, decorating doorframes with its evergreen stems and red or white berries.

How it went from being literally named in old Anglo-Saxon “bird poop on a twig” (we’ll get to that) to being considered a place for a Christmas kiss is the source of some speculation. The most prevalent thought is that mistletoe is a very fertile plant, so you can make the logical jumps from there.

Here in Colorado, we have the Southwestern Dwarf Mistletoe, a stubby, leafless species, living exclusively on Conifer trees, mainly Ponderosa Pine and Lodgepole Pine, more yellow and orange in color, and not so lovely to decorate with. It is extremely slow growing, so a tree showing fruiting bodies has already been harboring the plant beneath its bark layer for 2-5 years.

Is it here in the Foothills?

You bet. These photos were taken not far from my location in Bailey.

How does it get to its host tree?

A well-established plant will fruit out in berries that are filled with a sticky water substance. Hydrostatic pressure builds until the berry bursts sending the sticky seed at up to 60 mph(!) in search of the next host or branch to land on. This burst can send a seed 3 to 12 feet away. Many seeds simply fall to the ground to dry up, without a living host, they will die, but many others land on the bark of the nearest Ponderosa Pine branch of the same tree or a nearby tree, the sticky substance helps it hang on. This video shows the seeds bursting out of their pods.

The seed begins by sending down ‘haustoria (similar to roots) sinkers’ deep into the bark layer downward and laterally as well, to the phloem and xylem layers where the life force of the tree pulses with water, glucose, and other nutrients. Sinkers are sent deep into the inner xylem layer of the branch. In the 2-5 years of this slow action, the parasite becomes very well-established in the tree, with only a slight swelling noticeable from the outside.

Once established, the plant begins to send outward shoots from the bark to produce the fruiting berries. (Don’t try one, they are poisonous to humans.) The ripe berries then explode and those seeds begin the process on another branch.

The other option for seed spreading is by birds either carrying a seed stuck to their feet or eating the berries and then pooping on a branch. So, here is where the name ‘Mistletoe’ came to be: the old Anglo-Saxon word for dung is ‘mistel’ and twig is ‘tun’, so the plant that grows from ‘dung on a twig’ (poop on a stick) in time went from ‘mistel-tun’ to ‘mistletoe’. It loses some Christmas-y feel now!

Does this harm the tree?

YES - Each branch that is infected becomes weakened. The branch produces less photosynthesis and deforms new growth on that branch. As it spreads to more branches, the tree produces less and less food and eventually starves. It is a slow death that is very minor in the initial stages. Death from the mistletoe infection alone can take over 60 years. However, as the tree weakens, bark and pine beetles find it and feast, accelerating its demise.

Some areas such as near the Bogus Basin Ski Area in Idaho (see video link in sources) have severe cases of mistletoe infection made worse by bark beetle, causing them to take drastic measures to control the infection and stop the spread of mistletoe. Clear-cutting and the grinding up of the most infected trees has been their method starting in 2019. Long-term analysis will determine the effectiveness of this course of action.

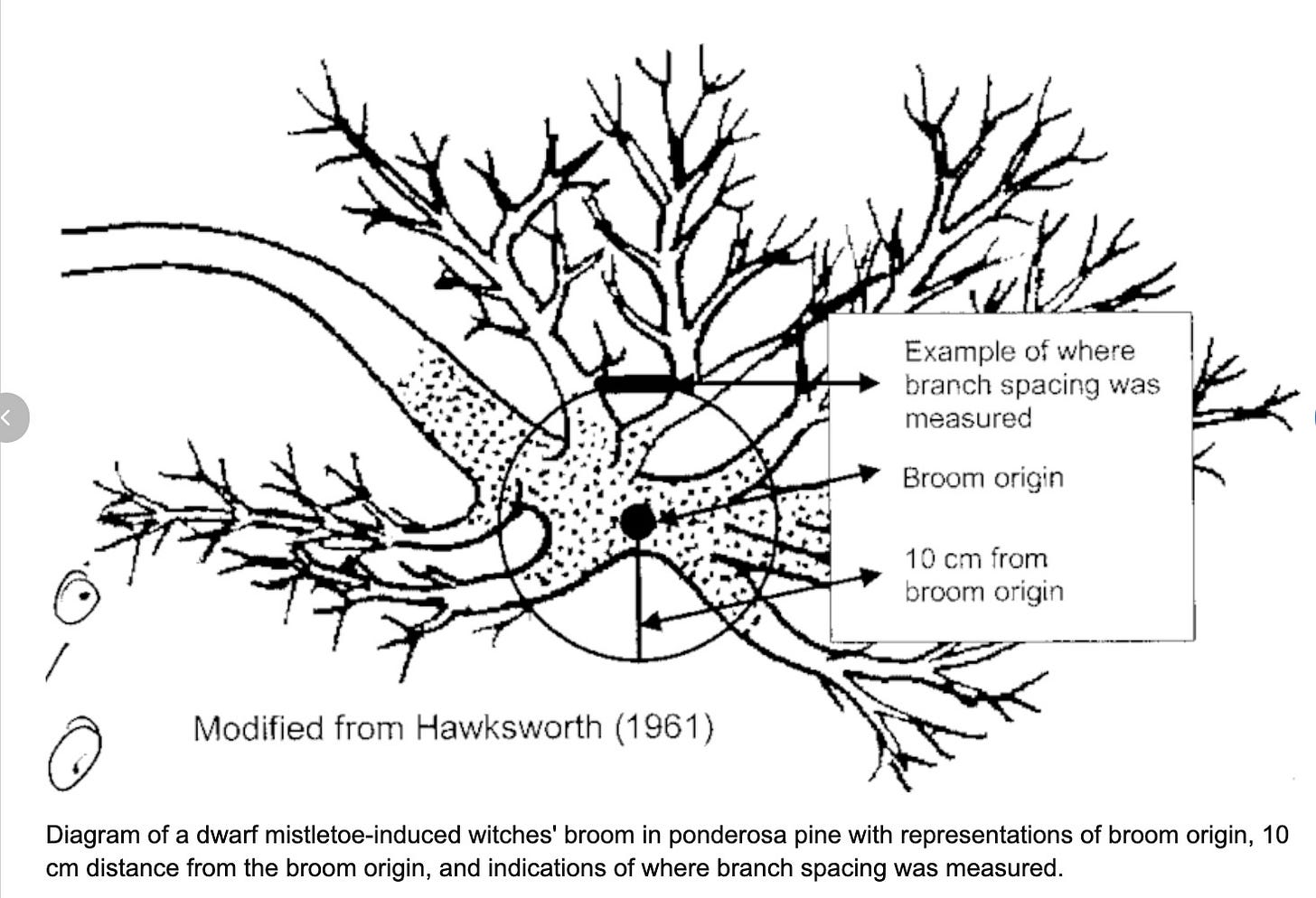

The Witches’ Broom

The primary deformity that occurs in growing branches is a mass of tangled growth that radiates from approximately a 10cm radius out from the infected area causing a tangled mass of branches and needles. The infection hijacks the tree’s resources causing focused, rapid growth of the entanglement. Branches become tightly intertwined.

This is horrible! Can’t something be done to stop it?

Cutting an infected branch can slow the spread. A dead branch equals dead mistletoe.

Removing the entire tree that is severely infected is often the solution.

The tree may respond itself, cutting off the supply of water and nutrients to the branch allowing it to die off and ‘self-prune’. Dead branch, dead mistletoe.

There are some sprays and other treatments used by foresters and arborists to inhibit the seed production. These require yearly re-treatments.

But - there’s more to the story……

Benefits to the other creatures, plants, and humans

- The definition of ECOLOGY is: the branch of biology that deals with the relations of organisms to one another and to their physical surroundings.

What is a very slow deterioration for the tree, is a benefit to the creatures that interact with it.

Mule deer, Abert Squirrels, porcupines, elk, and chipmunks will eat the mistletoe shoots.

Witches’ brooms provide platforms for bird and squirrel nests.

Many birds and squirrels make nests directly in the witches’ broom, including wrens, chickadees, pygmy nuthatches, mourning doves, spotted owls and 64% of Cooper’s Hawks nests were found in witches’ brooms.

Several species of butterfly depend on the parasite as well. They lay their eggs on the mistletoe and the young caterpillars eat the shoots. Adults will feed on the sticky seed nectar, as do some bees.

Many birds eat the berries, including robins, chickadees, mourning doves, and bluebirds.

Mistletoe and the Ponderosa Pine have evolved together for over 20,000 to likely millions of years, based on the fossil records. They survived long before mankind decided any intervention was needed.

A tree that has died becomes a snag that will house many nests, and feed many birds who come to feast on the decomposer insects that get to work on the tree. In time, the snag fully returns to the earth to cycle nutrients to the next generation of trees.

New research is underway currently showing promise in extracts from the mistletoe as being effective in the treatment of certain cancers, with less toxicity to humans than standard chemotherapy.

Summary

While Dwarf Mistletoe threatens the health of the infected Ponderosa Pine, its overall detriment is curbed by the additional relational elements of its environment. Providing food and shelter for squirrels, deer, birds, and butterflies, and potential health benefits for humans demonstrates that very little in nature can be labeled as either ‘good’ or ‘bad’. Additionally, very little is wasted. There are ecological ripples causing often unexpected connections and results. Mistletoe is a part of a healthy ecosystem and several species are even now listed as endangered.

This encourages us to seek broader connections and relations, slow judgment and reaction, and allow it to feed our deep, human hunger for wonder.

John Muir knew this well:

“When we try to pick out anything by itself,

we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe."

Sources:

- All photos copyright AbertEssays unless otherwise noted. May not be used without permission from the site owner.

-Ponderosa: Big Pine of the Southwest, Dr. Sylvester Allred, University of Arizona Press

- Many thanks to Dr. Allred, Univ of Northern Arizona, for advisement on the facts noted here.

- https://static.colostate.edu/client-files/csfs/pdfs/DMT.pdf

- https://csfs.colostate.edu/forest-management/common-forest-insects-diseases/dwarf-mistletoe/

- https://www.colorado.edu/asmagazine/2021/12/19/forensic-analysis-dead-ponderosa-pine

- https://www.britannica.com/plant/mistletoe

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/poop-tree-parasite-mistletoe-180967621/

- https://forestpathology.org/parasitic-plants/dwarf-mistletoe/

- https://blog.nwf.org/2012/12/12-things-to-know-about-mistletoe/

- http://www.landandwater.com/features/vol49no6/vol49no6_1.html

You can find The Abert Essays, along with my ‘Encounters’ posts, on my social media sites: https://linktr.ee/abertessays

Very interesting article!